24 Jan How Wofford Became Pennsylvania’s Senator

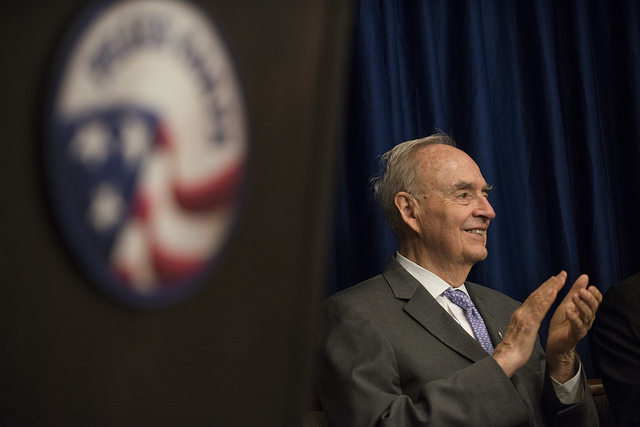

Former United States Senator Harris Wofford of Pennsylvania died on Monday. The trailblazing civil rights leader marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, worked in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations, and served as the fifth president of Bryn Mawr College. In 1991, following the tragic death of Senator John Heinz, Governor Robert P. Casey appointed Wofford – a fellow Democrat and his Secretary of Labor and Industry – to the vacant seat.

Wofford was not Casey’s first choice. At the urging of his then obscure campaign manager James Carville, the Governor offered the seat to businessman Lee Iacocca.

Below is the story, in Wofford’s own words, of how, with a little help from First Lady Ellen Casey, he got to be the Distinguished Gentleman from Pennsylvania:

… an assistant of mine, when I was secretary of labor and industry in Harrisburg, who says that he heard on the radio driving his car that John Heinz had crashed and died, along with a number of young kids, in an elementary schoolyard very near my home in Bryn Mawr. And he stopped the car, went into the nearest bar and said, “I’ve got to borrow your phone for a minute, can you” – this is pre-cell phone, I guess, isn’t it, because he’s a big cell phone man now – he said, “I’ve got to call the next senator from Pennsylvania.” The bartender didn’t know what he was talking about. And he tracked me down and interrupted me at the faculty club, and it changed the conversation to, well, from his point of view and some of the people at the seminar about, “Now how do we get you appointed to being senator?”

Now Casey said to the Cabinet, “I don’t want anybody maneuvering or stirring up or beating the drum for me to pick them, I want this to be a period of mourning for” – I forget how many weeks he said – “I’m going to be doing thinking while I do it, but I don’t want any politicking on it,” and I was resolutely following his instructions. Two days later or something, he said, “How well do you know” – whatever this guy’s name was – and I didn’t remember his name at all. And he said, “You must know him, come on now.” And I said, “No, why?” He says, “One of the biggest donors in the Democratic Party, and a state committeeman maybe, and he owns the Coronado Hotel.” I said, “Never heard of him.” “Well why would he have written this wonderful letter about you, this just stunning letter, if you don’t know him?” I said, “I have no idea.”

And the next day he said, “I have another couple of letters.” And he believed me that I was not doing anything, I think, because he tended to believe that I told the truth. And I really had no guess where these were coming from; they were from major donors of the party, most of whom I didn’t know at all. And about a week later Alan Cranston [the U.S. Senator from California] called me and said, “From the moment I heard about John’s death, I started writing my major donors, or calling them, and persuading them that you should be the senator and they should write Casey, and I helped them write their different letters, right?”

…

And interestingly enough, [lack of money] was said to be the biggest obstacle to Casey appointing me. His wife – and some other people – but his wife said, “Of course Harris is the one that you should appoint.” We were at Covington & Burling together, and [Casey] very much appreciated my civil rights role particularly.

And later I heard that he told his wife and other people that were speaking for me that, “It can’t be Harris because, I’ve just gotten this multiple disease problem, I’ve just raised this money for my reelection and I was worn out doing it. Harris has never raised political money, has none himself, and it has to be a rich person. Almost no one has a chance to beat Thornburgh, who they’re going to send back to reclaim the seat.” No Democrat had won a Senate seat twenty-nine years since Joe [Joseph S.] Clark. And he said, “It has to be [someone] rich, and it has to be somebody who’s young in case there’s a fluke, they win, so they can hold the seat, and Harris is sixty-five, and it has to be from western Pennsylvania, because that’s the only way we can have a dent in Thornburgh.”

…

And then [James] Carville, who we had picked to run Casey’s gubernatorial campaign but hadn’t gotten much publicity for that when Casey won – I was Democratic Party chair at Casey’s request full-time for six months during the campaign and helped pick Carville – Carville persuaded Casey to offer the job, to try to get Lee Iacocca to take it. He hadn’t lived in Pennsylvania for decades, but he had ties to Lehigh or one of the eastern universities, he wasn’t west, he was rich, but he also was old. And Carville said he’d got it all greased, and the only thing that Iacocca said to Carville when he flew out was, “You have to get Casey to come and offer it to me here, I’m not going to go and meet him somewhere else.” And so they persuaded Casey to fly out, the whole press got wind of it, had huge headlines, he’s flying out to – And he said, “I need twenty-four hours,” and he turned it down. And allegedly Ellen turned in bed and said, “Now it has to be Harris,” so that’s how I got to the Senate.

From an Interview with Harris Wofford by Brien Williams for the George J. Mitchell Oral History Project

No Comments